From Tool to Tutelage: The Trap of American Proprietary Systems

Digital Sovereignty: The Real Cost of Dependence

There are infrastructures that one day cease to be tools and become constraints.

Technical choices that, through being renewed by inertia and/or laziness, mutate into dogmas.

Operating systems that no longer serve the organization but capture it.

Microsoft Windows belongs today to this category: no longer a simple operating system, but a political, economic and cultural fact.

I propose a cold, argued, clinical diagnosis on the trajectory of a system that has become mechanically losing, and on the shared responsibilities that have led Europe (administrations, companies, hospitals, strategic industries) to lock itself into structural dependence.

I finally propose a realistic way out, already partially there, that many still pretend not to see.

Windows' failure is not primarily technical. It is cultural.

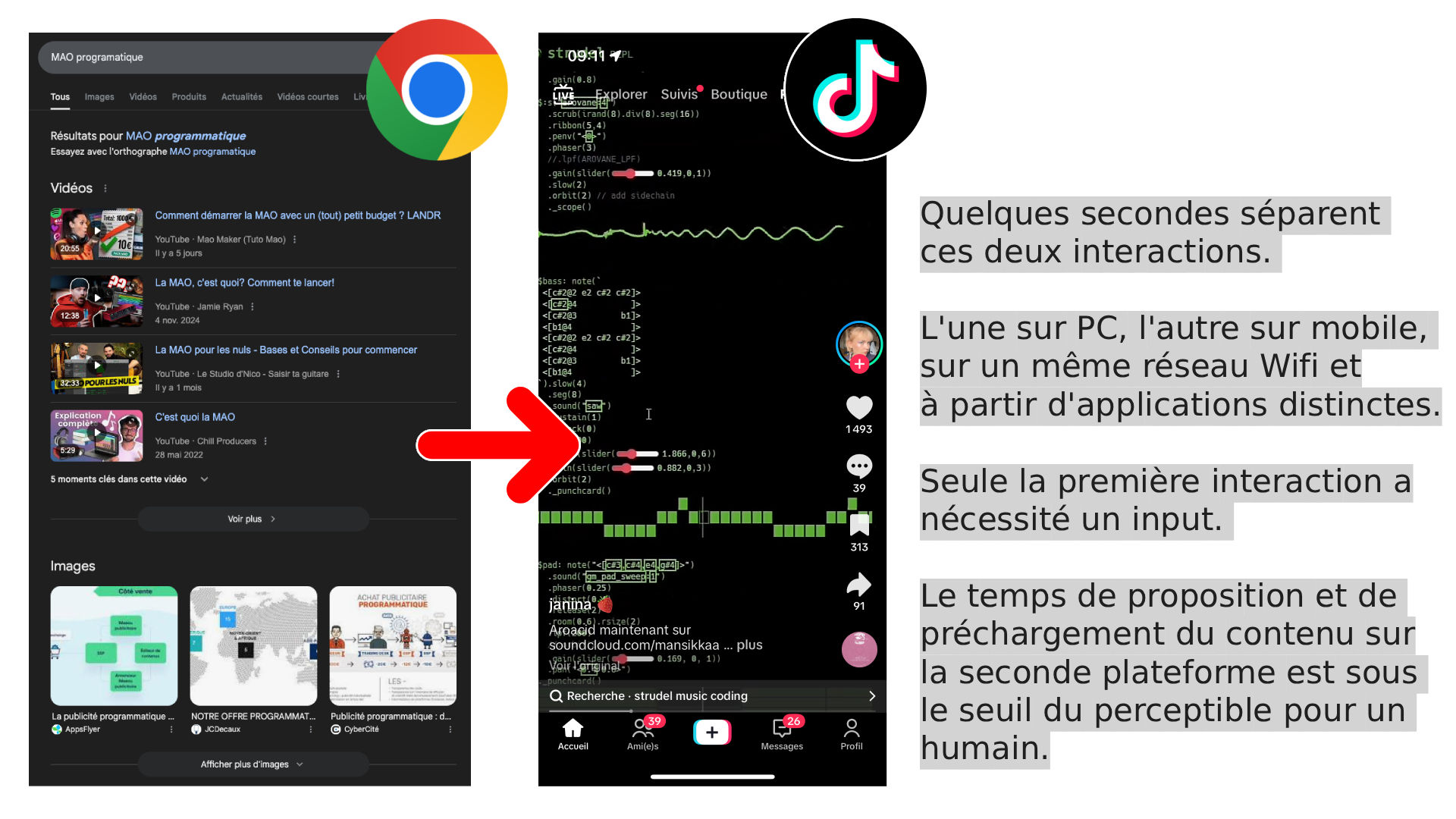

It stems from a relationship to software that privileges market domination over intrinsic quality, functional stacking over architectural coherence, communication over mastery. Microsoft never truly conceived Windows as an operating system in the strong sense of the term, but as a capture platform. Capture of third-party publishers, capture of end users, capture of entire organizations through backward compatibility and fear of change. This strategy worked for decades because it relied on a precise context: the explosion of individual PCs, the absence of perceived alternatives, and a general tolerance for technical approximations as long as "it starts" and "Outlook opens".

But this model is now reaching its physical and logical limits. The facts are now public, documented, repeated, to the point that only bad faith still allows talking about isolated incidents. Windows has become a stack of historical layers never truly purged. Components inherited from the 1990s coexist with modern components, obsolete APIs remain exposed to preserve applications long dead, and each modernization attempt results in a makeshift compromise.

The result is a system of extreme internal complexity, impossible to audit seriously, impossible to secure properly, impossible to master without an army of patches, antiviruses, EDRs, GPOs, PowerShell scripts and certified consultants.

It's no accident that the Windows ecosystem permanently generates its own patch market: it needs it to survive. Cumulative updates deployed at forced march, sometimes without real possibility of freezing in critical environments, have repeatedly caused massive service interruptions. Boot loops, broken drivers, printing paralyzed for weeks, application incompatibilities discovered in production: the "botched update" is no longer the exception, it's an integrated operational risk, accepted as fatality.

Few CIOs still dare admit it publicly, but many now organize their calendars around the fear of Patch Tuesday.

To this cultural failure is added structural connivance with bad actors. Windows has become the environment of choice for industrial malware, organized ransomware, opportunistic mass espionage. Not because it would be intrinsically more "hackable" than any other system, but because it concentrates uses, privileges and naivety. Software monoculture is a disaster accelerator, and Microsoft is its architect. Each critical flaw discovered in Active Directory, in SMB, in Exchange or in the print engine is not an isolated accident: it's the expression of a model where massive exposure is structural. The promise of security "through the cloud", hammered for a decade, has solved nothing. It has even aggravated certain propagation vectors. The waves of ransomware that hit European hospitals, local authorities and industrial SMEs have almost all exploited the same chains: compromise of a Windows workstation, privilege escalation via Active Directory, automated lateral encryption.

The extreme standardization of the Microsoft environment has enabled industrialization of digital crime on an unprecedented scale. It has simply moved the problem to even more opaque layers.

The concept of "too big to fail" has mutated here into "too big to succeed". Microsoft is prisoner of its own size. Each significant evolution threatens a gigantic ecosystem of partners, certifications, contractual dependencies. Each decision is slowed by the need not to offend anyone, except the end user, docile adjustment variable. The system thickens by sedimentation, never by refactoring. But an operating system cannot sediment indefinitely without transforming into a swamp.

Faced with this state of affairs, the responsibility of European information systems management is heavy. For years, they adopted Windows and the Microsoft ecosystem not by enlightened choice, but by intellectual comfort and fear. Fear of stepping outside the framework, fear of not finding skills, fear of assuming a political decision under the guise of technical. The discourse is always the same: "it's the standard", "everyone does it this way", "we can't take that risk".

This reasoning is precisely what creates systemic risks.

CIOs have accepted, often without understanding them, architectures of extreme fragility. Active Directory forests that have become single points of compromise. User workstations overloaded with implicit privileges. Imposed updates, uncontrolled, sometimes destructive. Software dependencies so deep that a simple version change becomes a multi-million project.

All this is known, documented, experienced daily by field technical teams.

And yet, denial persists at the top of executive committees.

This denial is also ergonomic. The Windows UX in professional environments is painful, unstable, inconsistent. It imposes permanent cognitive gymnastics on users, incessant interruptions, unpredictable behaviors. This painfulness is not anecdotal: it has a human cost, an economic cost, an organizational cost. It is however rarely integrated into strategic decisions, as if the user experience of public servants, engineers, caregivers was secondary to the sacrosanct Office compatibility.

Even more serious, CIOs have largely underestimated (or voluntarily minimized) the geopolitical dimension of their choices. Massively adopting an operating system, cloud services, collaborative tools subject to American extraterritorial law is not a neutral decision. The Cloud Act, data collection practices, opaque judicial injunctions are documented realities.

Continuing to build critical information systems on legally foreign foundations is either incompetence or responsibility avoidance.

The European Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act arrive late, and struggle to counterbalance an already deeply rooted dependence.

Technical lock-in is now coupled with assumed economic strangulation. The price increases imposed by Microsoft on Azure and by Broadcom since the capture of VMware no longer represent market evolution but systemic abuse of position.

Licensing grids change without real notice, billing metrics are redefined unilaterally, and multi-year contracts become budgetary traps. In many organizations, costs explode by 30 to 300% without corresponding value creation, without measurable security gain, sometimes even with loss of operational control. Compliance auditing is no longer a governance tool, but a permanent threat, used to remind the captive client of the asymmetry of the power relationship. Broadcom for example has chosen frontal brutality by eliminating any alternative to subscription and making intermediate offers disappear; Microsoft practices the same extraction, more diffusely, by indissociably linking OS, cloud, identity, security and collaboration.

The message is clear: leaving costs dearly, staying costs even more.

This rent logic, incompatible with any serious strategic planning, transforms information systems management into dependence managers rather than value architects.

It's time to say things clearly: persisting in this path is no longer prudent conservatism, it's a strategic fault. Repeated incidents on Microsoft cloud infrastructures, and particularly on Azure, should finish dispelling illusions. Global outages affecting authentication, prolonged unavailability of critical services, breaks in hosted CI/CD chains: when a supplier becomes both the OS, directory, messaging, collaboration and cloud, each failure takes on a systemic dimension. Externalizing the core of the information system this way amounts to accepting structural loss of control.

A fault towards citizens, companies, European sovereignty.

A fault that history will remember severely.

The way out exists however. It is neither utopian nor marginal. It's called free software, and more precisely today GNU/Linux in its contemporary maturity. The Linux world of 2026 has nothing in common with the artisanal and elitist beginnings. It is robust, industrialized, tooled. It runs most of the Internet, almost all high-performance computing, a large part of critical global infrastructures.

It has proven, through facts, its capacity to evolve, to secure itself, to be audited.

Unlike Windows, GNU/Linux is based on a culture of transparency, responsibility and mastery. The code is readable, modifiable, auditable. Dependencies are explicit. Updates are controllable. Architectures are designed for privilege separation, for resilience, for sobriety. The myth that Linux is reserved for a technical elite is maintained by those who have an interest in maintaining the status quo. In reality, modern desktop environments, free office suites, open collaborative tools have reached a level of maturity largely sufficient for the vast majority of professional uses.

The question is therefore not technical. It is cultural and political. Leaving Microsoft dependence requires massive, assumed, organized acculturation. Training decision-makers, not just technicians. Giving CIOs strategic backbone again. Accepting a period of transition, cohabitation, learning. Investing in local skills rather than foreign licenses. Creating value in Europe, instead of exporting it in the form of royalties.

This transition goes against the ambient techno-bullshit, the headlong flight towards turnkey, opaque, supposedly magical solutions. It also forces us to look lucidly at other actors long perceived as refuges.

Apple, for example, still cultivates an image of elegant dissidence, but now aligns without complex its strategy with the hardest American political and commercial interests.

Since Steve Jobs' disappearance, product culture has given way to a logic of lock-in, opportunistic regulatory submission and docile communication. Public demonstrations of allegiance to American political power, including the most brutal, should suffice to recall an obvious fact: Apple is not a sovereignty alternative, but another form of dependence, more polished, more expensive, and just as opaque. It requires courage. But it is the condition for real digital power. Sovereignty is not decreed, it is built through concrete choices, sometimes uncomfortable, always structuring.

This is not about demonizing Microsoft by ideological posture. It's about noting that an American private actor, however performant elsewhere, has no objective reason to align its interests with those of Europe. Continuing to entrust it with our nervous systems is a gentle, polite, contractualized abdication.

Getting out is an act of maturity.

Europe has the skills, researchers, engineers, communities to succeed in this shift.

It already has the building blocks. What is still missing is not technology, but the will to break and lucidity about what we refuse to assume as a failure of all our critical infrastructures if we do not act immediately.